When people ask me what the most unusual thing about living in a country at war is, I say it is how normal things are. Life in Lviv during the war is one of constant and extreme contradictions.

I must of course preface this post by acknowledging that these are only the experiences of a foreign volunteer, who cannot speak to the experiences of Ukrainians themselves, and that these experiences are limited to one of the safest cities in one of the safest regions of Ukraine. I have not lost a friend or relative to this war, nor have I experience direct conflict. Ukrainians, especially in the East, will have a much different experience to me.

I’ll start with the normal. Almost every day, I awake at my own pace. I make or buy breakfast, and head to “work”. My evenings are spent with friends, going out to dinner in one of Lviv’s amazing restaurants, enjoying the company of locals and foreigners alike in one of Lviv’s many bars. At weekends I take time to explore the city, to visit cultural events and museums. I have gone to music concerts and festivals. People have birthday parties with their friends, go shopping for books, walk their dogs, live their lives.

Lviv is still despite the war, or perhaps in fact because of it, a city of tourists. Though now they are not foreign tourists seeking a getaway in a beautiful, cheap city. It is Ukrainian tourists, looking for a taste of normalcy away from their homes closer to the frontlines. Ukrainians who want to wake up to an alarm, not an air alert. Ukrainians who want a reminder of what life was like before the constant barrage of Russian bombs that falls on Zaphorizia, Kherson, and Kharkiv.

When spending time in Lviv, especially a short time, one can miss many of the signs of the war. Weeks can pass without an air alert. Avoiding the central square during the day means you can miss the funeral processions for fallen soldiers. Early nights mean that curfew isn’t a factor beyond the nights being quieter (when the missiles aren’t overhead at least). With little effort, one can truly be lulled into a sense of normality.

This does not mean, however, that the normal lasts forever. You can be enjoying a walk in the park, when the air alert begins and you need to see if you can make it to a shelter in time or just hope nothing is actually coming your way. You discover that while a candlelit dinner is romantic; cooking by candlelight because the Russians have bombed your local power plant is very impractical. Your catch up with a friend reveals that their sibling/relative/partner/old school teacher has been killed or wounded at the front. A trip to a cafe includes displays of war art. Your concert is paused half way through for the band to auction used military equipment to raise money for ZSU.

Sometimes, the shift between normalcy and abnormality can be jarring. You can be experiencing a normal event that could be happen anywhere in Europe, and then a piercing reminder of the war shoulders its way into view.

The most perfect example of this is the image below. I took it while attending “Dice Con”. It is an annual conference where Dungeons and Dragons fans, cosplayers, comic writers, and other nerds can gather, buy games, and discuss their hobbies (so of course I couldn’t resist attending). Here I waited to buy custom dice from LozaDice while a woman dressed as an elf looked at his products. It was a scene that, while not everyone would consider normal, could happen in any other European city.

This scene of “normality” took place at the Lviv Art Palace, which at the time was also hosting an exhibition of paintings and photos that captured the war raging in the East. It displayed both life and death on the frontline. The image directly behind the stall is of the final moments of Oleksandr Matsievskyi’s life before he was executed by Russian murderers.1

This image encapsulates my feelings about life in Lviv. It is normal, and then it is not. It could be anywhere in Europe, but it isn’t. If you want to avoid signs of the war, you can. If you look for them, they are everywhere, just around the corner or beneath the surface.

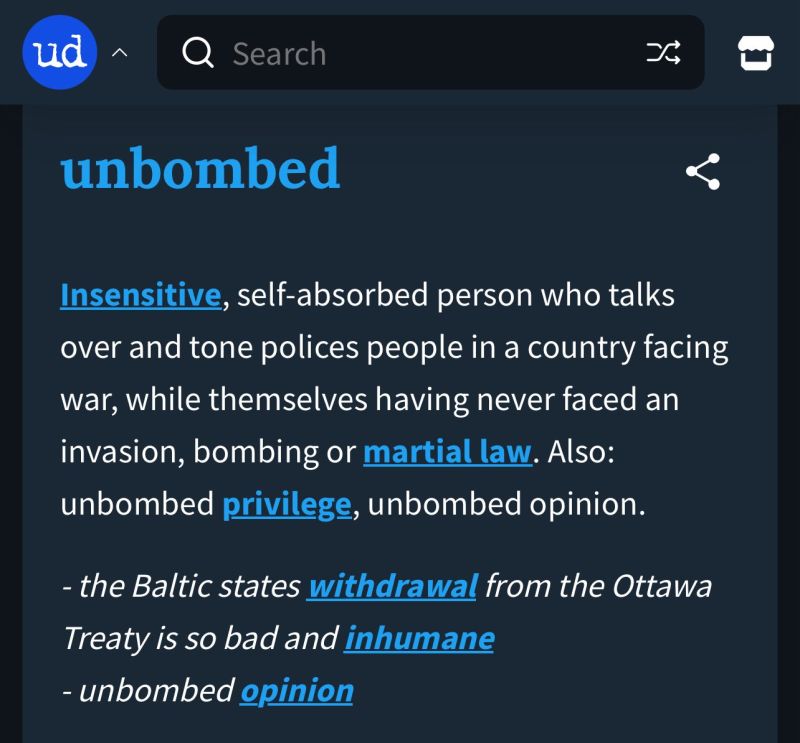

This could be anywhere, because this could happen anywhere. War can come for any of us. Russia’s ambitions to not end with Donetsk, nor do they end with Ukraine. This war is all of ours, most in the West just don’t want to acknowledge it yet. I only hope they do before it is too late, both for Ukraine and for them.

- Oleksandr Matsievskyi was executed in late 2022/early 2023. A video of his execution was published by his murderers, in which he is shot dead in a grave he was forced to dig himself. It is one of the most brutal Russian war crime videos, and stands out for its brutality, and Oleksander’s resilience: he shouted “glory to Ukraine” immediately before his murder, in the face of his killers. ↩︎

Leave a comment